“We attempt to visualize the eventfulness of a universe that is an electro-dynamic plenum in the representational clichés evolved at a time when statically-conceived, isolable ‘objects’ were regarded as occupying positions in an empty and absolute ‘space.’ Visually, the majority of us are still ‘”object”-minded’ and not ‘relation-minded.’ We are the prisoners of ancient orientations imbedded in the languages we have inherited…The reorganization of our visual habits so that we perceive not isolated ‘things’ in ‘space’ but…the relatedness of events in space-time, is perhaps the most profound kind of revolution possible — a revolution that is long overdue not only in art, but in all our experience.”

Gyorgy Kepes, Language of Vision (1944)

“‘By contemplating the optical-physical appearance, the ego arrives at intuitive conclusions about the inner substance.’ The art student [is] to be more than a refined camera, trained to record the surface of the object. He must realize that he is ‘child of this earth; yet also child of the Universe; issue of a star among stars.’”

Sybyl Moholy-Nagy, introuction to Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook

“As soon as we open the door, step out of the seclusion and plunge into the outside reality, we become an active part of this reality and experience its pulsation with all our senses. The constantly changing grades of tonality and tempo of the sounds wind themselves about us, rise spirally and, suddenly, collapse. Likewise, the movements envelop us by a play of horizontal and vertical lines bending in different directions, as colour-patches pile up and dissolve into high or low tonalities.”

Wassily Kandinsky, Point and Line to Plane

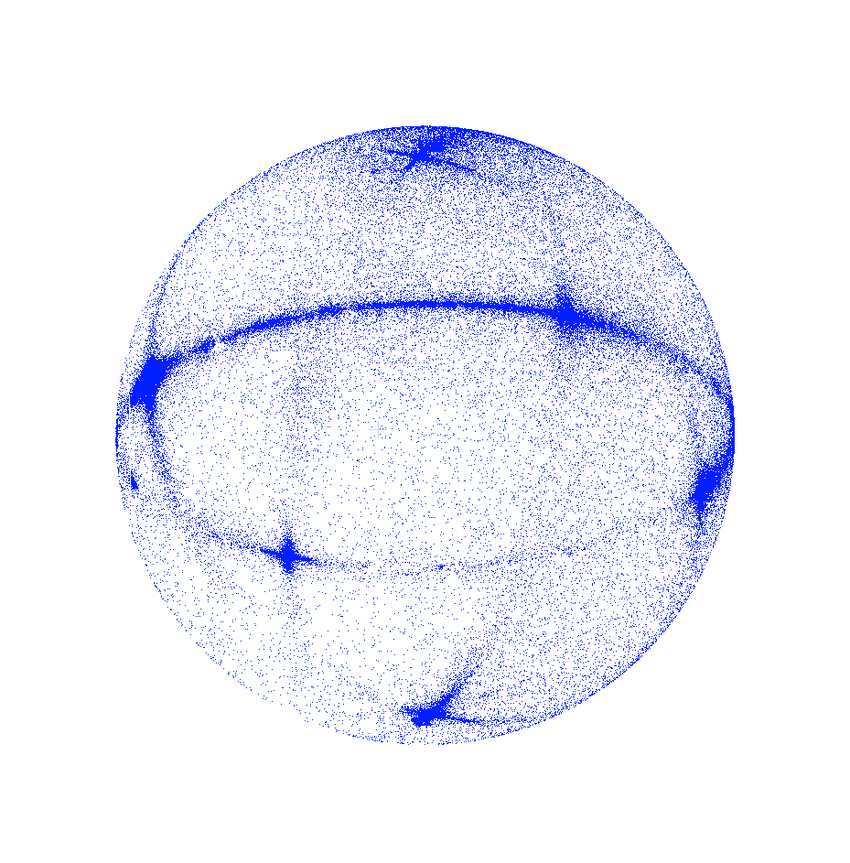

What do we look at when we look at the planet? What visual heuristics structure the way that the earth becomes familiar to us?

This project departs from the notion that the images available to us are extremely limited — limited not in a purely aesthetic sense, but in the epistemic, relational, and technological paradigms in which images are produced and circulated. The image of the whole earth from space is passed down to us from a particular moment in time: an era in which it made sense to apprehend the world, and each thing inside it, as separate from the entity who sees it.

This image rests comfortably in the history of linear perspective, a perspectival system developed by Alberti and Brunelleschi at the beginning of the 15th century. Linear perspective was a technique of representation that, like all others, reflected and propagated a particular understanding of the world and how to know it. This perspective presented the visible world as a unified pictorial space, ordered and rationalized in the terms of modernity’s burgeoning conception that the world could be systematically understood and explained.

But what kind of thing is a planet? How can it any longer make sense for us to see it as this kind of object, separable in space from this kind of viewing subject? Linear perspective now reveals itself as fundamentally inadequate to how we must know the world today: interrelated, entangled, only provisionally knowable, and never able to be grasped by a single perspective.

The stakes of the emerging concept of the planetary are high: our ability to correlate the destructive history of humanity with a future that vindicates it, our attempt to integrate what we take to be the given natural world with what we add to it in the form of built objects and environments, our hopes that we can learn to live together, not as a family of nations but as billions of things truly at home.

What role do images play in shaping how it feels to be a planetary thing? How can we reorganize our visual habits to enact the realities we dream of and are working for?

This page is a visual/textual exploration inspired by the art and design handbooks written by Kepes, Klee, and Kandinsky. Like these thinkers, it contends that visual concepts are deeply philosophical, that in seeing the world we also actively create it. Images not only as a form of art, but also as a form of thought. And as the boundaries of the visible are expanded through new imaging technologies — in this case through the increased use of satellite imagery — there arise new opportunities to know and feel the world differently.

It is one small piece of an attempt to move toward the new way of seeing necessary for our entangled existence.

figure/ground

We are accustomed to seeing only what is separable from our bodies in space; seeing means distance. When it comes to images of the planet, conventions of visuality exacerbate the distinction between subject and object. The disembodied perceiver stands, or rather floats in free fall, at a predefined distance from the planet being perceived. This is a view from nowhere, a position occupied by nobody and theoretically occupied by anybody.

This perspective deludes us into believing that the planet is a thing in space, a figure upon a ground. In actuality, thing and context are resolutely interwoven.

James Elkins writes in The Object Stares Back, “there is no such thing as an observer looking at an object if seeing means a self looking out at a world.” Observer and object are dynamically intertwined. Yet our images for the planetary are philosophically naive; they assume a distance between perceiver and perceived, a condition that becomes impossible when we conceive of ourselves as actually, structurally part of the planet.

There is no clear and agreed-upon boundary between the earth’s atmosphere and outer space. No clear physical demarcations that separate the earth as an entity with the context that holds it. Rather, the earth is having a constant conversation with its atmosphere. And like all conversations, it is a process of un-selfing, of entities ridding themselves of the delusion of identity as containment.

How can we train ourselves to be attentive not to the complete figures and forms, but to the interstices, the in-between spaces?

lines and curves

A line implies continuity; a straight line will continue onwards, a curved line will continue to be curved at the same angle, and a waved line will move forward at the same rhythm or frequency.

A curved line, in bending back toward itself in a complete circle, becomes a container in two dimensions. Adding centripetal and centrifugal force, this circle becomes a sphere.

The representational system of linear perspective does not account for the curvature of the earth. Nor does it account for the gentle topographies of ocean and ground. Yet the horizon of perspective structures the way we navigate and orient as we move across the planet. Everything that we see compositionally is in reference to this line.

We experience the curvature of the earth through the flat lines of two-dimensional photography

A line is a boundary marking a form in space, but a line also cuts together. A line is a meeting place. A horizon as a weaving of earth and sky.

surfaces

When we look at images of the planet, we are seeing only its surface. Within these representations of surface, we can read time, movement, change.

Psychologist J.J. Gibson relates the relationship between an object and its surface:

“The surface is where most of the action is. The surface is where light is reflected or absorbed, not the interior of the substance. The surface is what touches the animal, not the interior. The surface is where chemical reaction mostly takes place. The surface is where vaporization or diffusion of substances into the medium occurs. And the surface is where vibrations of the substances are transmitted into the medium.”

The surface is an interface between elements or media. But is it a thing in itself? Leonardo da Vinci held that the surface, in being precisely the location where two entities meet, has no “divisible bulk” in itself. It is a conceptual object, not a physical one.

Gibson limits his analysis to opaque bodies, not those things we can readily see through. But the history of vision has rendered the insides of opaque bodies visible. The x-ray, sonar, magnetic resonance imaging — these technologies allow us to see what before, in a sense, did not exist. The transparency/opacity of an object seems to be the function of the way we look at it.

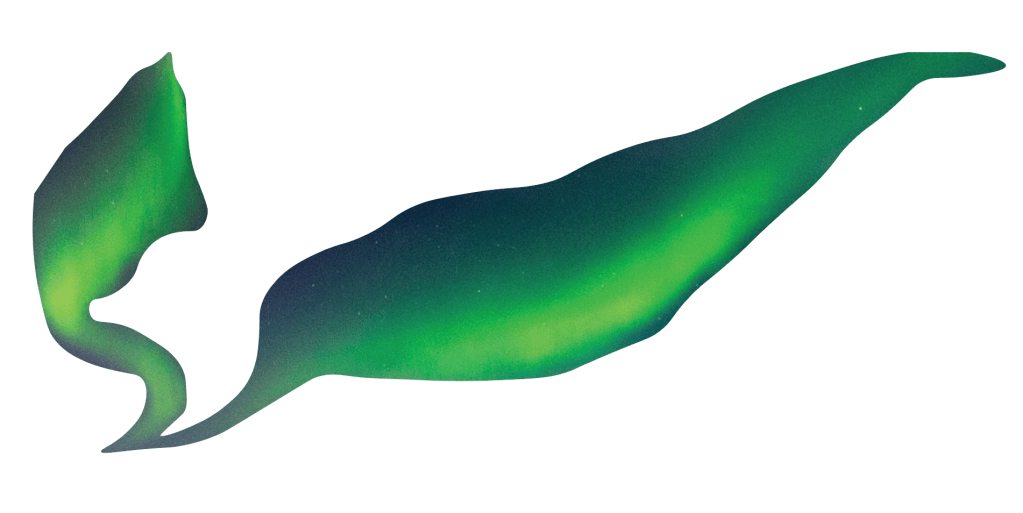

transparency

Transparency is a heuristic meant to spur the unfolding of new modes of critical visual engagement with the world. It presents a constellation of new concepts, new orientations for seeing/thinking/knowing.

Architect Kurt Ofer has proposed transparent drawing as a design practice and a mode of inquiry: drawing for maximal knowledge of an object, for holistic understanding of the object in space.

Moholy-Nagy writes: “Transparency means a simultaneous perception of different spatial locations. Space not only recedes but fluctuates in a continuous activity.” These superimpositions of form ‘transpose significant singularities into meaningful complexities,” creating “a rather causal interweaving of surface and the elements introduced to destroy the logic of this deep space.‘”

And Kepes: “If one sees two or more figures partly overlapping one another, and each of them claims for itself the common overlapped part, then one is confronted with a contradiction of spatial dimensions. To resolve this contradiction, one must assume the presence of a new optical quality. The figures are endowed with transparency; that is, they are able to interpenetrate without an optical destruction of each other. Transparency however implies more than an optical characteristic; it implies a broader spatial order. Transparency means a simultaneous perception of different spatial locations. Space not only recedes but fluctuates in a continuous activity. The position of the transparent figures has equivocal meaning as one sees each figure now as the closer now as the further one.”

He goes on to elaborate that transparency is the visual conception of a tendency that is coming to guide the activities of technology, psychology, philosophy, physical science, architecture, and the arts, which is to see integration and interpenetration in every domain and at every scale.

Transparency as an imaginative optics — a way to layer more knowledge inside of an image.

What might happen if we configure the planet as transparent? If a location were conceived not as coordinates on the surface of an opaque body, but as a moment within many different biogeochemical, microbial, and elemental moments?

Transparency enables a wider set of visual concepts that can be brought to bear on how we come to know the planetary, and thus how we come to constitute and live it.

proprioception/synesthesia

With machine vision, we have the ability to encode many different physical properties as images — radiation, electric charge, conductivity, or reflectivity, mapped onto the spatial distribution of visible light. The boundaries between visibility and invisibility are shifting, contingent upon technical potentialities and the contextual factors that enact this potentiality in a particular way.

Proprioception, first theorized in 1906 by English neurophysiologist and Nobel laureate Charles Scott Sherrington, describes the way that the body, through feedback loops unbeknownst to the conscious mind, becomes aware of its position in space. Location in space “outside” is intimately connected to sensory awareness of the space “inside.” How does the planet sense it self? And what would it mean for this sensing-of-itself to become experiential?

“Seeing” is expanded to frequencies and sensory modalities that are not visible through human sight alone. What is a planetary visuality that conveys machinic perspective without reducing it to familiar human visual heuristics?

motion

Nearly all philosophies of perception assume that when we talk about what we see, we are talking about what is a stationary observer’s visual field at a given time. But in actuality we are in constant motion at every level, at every scale. From the microorganisms that largely comprise life on earth and the movement of atoms, to the orbital dances and bending of spacetime.

How can an image contain motion?

“To say that a circle seen obliquely is seen as an ellipse is to substitute for our actual perception what we would see if we were cameras : in reality we see a form which oscillates around the ellipse without being an ellipse” -Merleau-Ponty, Cezanne’s Doubt

Kepes: “Thinking and seeing, in terms of static, isolated things identical only with themselves, have an initial inertia which cannot keep pace with the stride of life… Common sense regards rest and motion as entirely different processes. Yet rest is, in reality, a special kind of motion, and motion is, in a sense, a kind of rest. The plastic image can fulfill its present social mission only by encompassing this identity of opposing directions and referring it to concrete social experiences.”

Motion implies change, in the object as well as in one’s ability to relate to it.

Motion implies the ability to navigate, to orient, to situate. What alternative modes of mapping might be available to us?

time

“The act of drawing, knowing and understanding all sides of an object, so that the object is resolved and understandable, cannot be achieved without the element of time.” -Kurt Ofer

Linear perspective freezes time; it presents one viewpoint contained within a single moment. It also enables linear time — the idea that the course of events unfolds in a single direction.

What is an image that points to the simultaneous happenings, the superpositions, that lie beneath the human-observable world? Quantum physics tells us that the future no longer follows successively from the past, that the world is made up of phenomena, not objects.

What is a picture of time that does not universalize time, that does not collapse all histories and futures into a “homogenous empty time?” (Walter Benjamin).

information/code

Satellite images exist through a process of translation: from wavelength to electrical charge to digital signal to radio waves to binary code to numerical value to image.

What can we learn from the way that satellites transmit energy into imagery? What kind of sight is this? What is the particular entanglement between representational and operational images?

Information becomes the medium of visuality and design, but information is not an image in itself. Necessary acts of translation configure data into pictures that human eyes can interpret. How do we choose to process the non-visual, informational or conceptual dimensions of reality as images?

In the act of making the invisible visible, we are guided by habits of perception that are both externalized to and conditioned by the technologies that make the world into images.

What revolution in vision is required of us now to meet the changing conditions of life on earth? How must we see?